Riding crops are a common sight in arenas, warm-up rings and out hacking, but many riders are not entirely sure what they are for, how they differ from other types of whips, or how to use them fairly. Understanding what is a riding crop, how it is constructed and when to use it, helps you communicate more clearly with your horse and stay within modern welfare-focused rules.

This guide explains what a riding crop is, how it has evolved, the different types of crops and related whips, and how to choose and use one correctly as part of kind, effective riding.

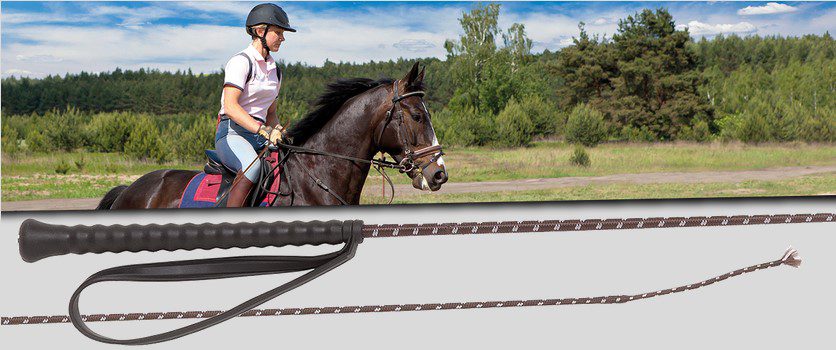

A riding crop is a short, firm whip designed to act as an extension of the rider’s leg. It is used to back up, or reinforce, a clear leg aid – not to replace it or to punish the horse. Most riding crops are between 70cm and 90cm in length, with a solid or semi-flexible shaft and a small leather or synthetic keeper at the end.

Used correctly, the crop allows the rider to give a quick, precise aid just behind the leg when the horse ignores or is slow to respond to the leg alone. It is a communication tool rather than a disciplinary one.

Although designs vary, most riding crops share the same basic components:

A good riding crop should feel light, balanced and easy to control while you are holding the reins. If it feels heavy, awkward or floppy, it will be harder to use accurately.

Whips have been used for thousands of years for herding and driving animals, but the riding crop as we recognise it today is a more recent development. Early riders often used simple sticks or canes; over time these evolved into more refined aids with flexible shafts and shaped handles designed specifically for mounted work.

By the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, riding crops had become an established part of equestrian equipment, particularly in hunting, racing and classical riding. As materials improved, crops developed from basic cane shafts to lighter, more responsive designs using steel, fibreglass and eventually carbon fibre. Modern crops combine traditional shapes with contemporary materials to provide a tool that is both durable and finely balanced in the hand.

“Whip” is a broad term that covers several different tools. A riding crop sits between a short jumping bat and a long dressage whip in terms of length and feel.

| Type | Typical Length | Main Use |

|---|---|---|

| Riding crop | 70–90cm | General riding, hacking, basic schooling. |

| Jumping bat | 40–70cm | Showjumping and cross-country, short and quick to use. |

| Dressage whip | 90–120cm (ridden) | Flatwork and lateral work; allows the rider to touch behind the leg without moving the hand. |

A standard riding crop is usually the most versatile option for everyday hacking and schooling. For more specialised work, a dedicated jumping bat or dressage whip often works better.

Understanding what a riding crop is also means understanding what it is not. A crop is not there to drive a horse forwards through force or to vent frustration. Its main purposes are:

The goal is always communication, not punishment. If a horse becomes worried, tense or resentful of the crop, it is a sign that something in the training or the way the crop is used needs to change.

Holding the crop correctly helps you stay balanced and give precise aids without disturbing the contact.

If the crop drags your hand down or feels awkward, it may be too long, too heavy or poorly balanced for you.

Good use of the crop is almost invisible to a spectator. A simple, fair sequence looks like this:

1. Ask with the leg first

Give a clear, positive leg aid and allow the horse a moment to respond. The horse should learn that the leg is the primary aid.

2. If there’s no response, add one clear tap

If the horse does not react, follow up with a single, quick tap just behind your leg on the same side. It should be firm enough to be meaningful but not aggressive.

3. Allow the horse to go forwards

As soon as the horse reacts by going forwards, soften your leg and hand slightly to reward that response. The aim is to encourage the horse to listen to the leg next time.

4. Avoid constant “tickling”

Repeated, low-level tapping dulls the horse and is often seen as excessive use. It is better to give one clear, fair aid than lots of nagging ones.

There are times when the kindest and most effective choice is not to use the crop at all. Avoid using it when:

If a horse repeatedly refuses or resists, it is usually more productive to look at saddle fit, schooling, rider balance or health issues rather than escalating with the crop.

Whip rules vary by discipline, but they all share a welfare focus. A few common themes:

Before competing, always check the current rulebook for your discipline so that your chosen crop or bat is legal for both warm-up and the competition arena.

When choosing a riding crop, think about both your own needs and your horse’s comfort.

1. Length

For general riding and schooling, a crop in the 70–90cm range suits most adults on horses. Smaller riders or those on ponies may feel more comfortable with a slightly shorter crop.

2. Weight and balance

The crop should feel light enough not to tire your hand, but solid enough that it does not flap around. A well-balanced crop will sit quietly until you choose to use it.

3. Grip

Look for a handle you can hold securely even if your hands are slightly damp. Leather wrap, rubber and textured synthetic grips all work well as long as they are not too bulky.

4. Keeper design

A broader, slightly padded keeper usually gives a clearer yet kinder feel than a very narrow, stiff end. In some jumping rules, a soft, padded keeper is compulsory.

5. Discipline rules

If you plan to compete, make sure your crop meets the whip rules for your chosen discipline so you do not have to swap equipment at the last minute.

Riding crops are relatively low maintenance, but a little care keeps them safe and effective:

A damaged crop can deliver uneven contact or even break unexpectedly, so it is worth replacing when it shows obvious signs of wear.

So, what is a riding crop? It is a short, well-balanced whip designed to act as a precise extension of your leg, used to support clear, fair aids rather than to dominate the horse. When chosen carefully and used sparingly, a crop becomes a subtle tool that improves communication and responsiveness without compromising welfare.

Understanding the construction, correct use and basic rule implications of riding crops helps you ride more effectively, stay within competition guidelines and build a more harmonious partnership with your horse.